| | by admin | | posted on 11th December 2025 in Quakers Through the Ages | | views 89 | |

Quakerism entered, endured, and reshaped the thirteen American colonies during the seventeenth century.

In the 17th century the thirteen colonies of English America were a mosaic of competing religious cultures, shifting allegiances, and fragile political structures. Into this unsettled world came the first Quaker missionaries in 1656, carrying a message of spiritual equality and direct communion with God. Their reception varied drastically from colony to colony, yet by 1700 Quakerism had touched almost every part of the Atlantic seaboard.

What follows is a survey of how Quakerism interacted with each colonial environment, from hostile Puritan New England to the tolerant harbours of Rhode Island, the experimental Quaker governments of the mid-Atlantic, and the scattered southern communities that persisted against the odds.

Massachusetts (founded 1630)

Quakerism’s American story begins dramatically in Massachusetts. When Ann Austin and Mary Fisher landed in Boston in 1656, Puritan authorities reacted with alarm. Harsh laws quickly followed: imprisonment, whippings, fines, banishment, and ultimately the executions known as the Boston Martyrs (1659-1661). Friends met secretly, but Massachusetts remained implacably hostile throughout the century.

Rhode Island (founded 1636)

In striking contrast, Rhode Island, founded on principles of religious liberty, became a sanctuary for Friends. By the 1670s, Quakers held public office in Newport and Portsmouth, and the colony’s open charter attracted ministers and settlers from across the Atlantic. Quakerism here grew peacefully and prosperously.

Connecticut (founded 1636) and New Hampshire (founded 1638)

Though less dramatic than Massachusetts, both colonies exhibited suspicion toward dissenters. Nevertheless, small groups of Friends emerged in coastal towns such as New London and Dover. They met quietly in homes, drawing strength from travelling ministers and their connection to meetings in Rhode Island.

New York (founded 1624)

Originally New Amsterdam under Dutch rule, the colony lacked Puritan uniformity but still discouraged dissent. After the English conquest in 1664, Quakers found greater room to organise. Long Island became a strong centre of Quaker life, hosting meetings that influenced the region for decades.

New Jersey (founded 1664)

New Jersey became one of the great Quaker experiments of the seventeenth century. Wealthy Quaker proprietors, including Edward Byllynge and later William Penn, acquired extensive lands. In West Jersey, settlers established townships shaped by Quaker governance: assemblies emphasised fairness, arbitration replaced litigation, and codes of conduct reflected Quaker values. Burlington and Salem became vibrant hubs of worship and commerce.

Pennsylvania (founded 1681)

The creation of Pennsylvania was the turning point for colonial Quakerism. Granted to William Penn as repayment of a royal debt, the colony was envisioned as a Holy Experiment in religious liberty and just governance. Thousands of Friends migrated from Britain and Ireland. They founded an ordered network of meetings, and Philadelphia, laid out with wide streets and public squares, became the beating heart of Quaker America.

By century’s end, Pennsylvania demonstrated the possibility, and the limits, of Quaker civil authority on a colonial scale.

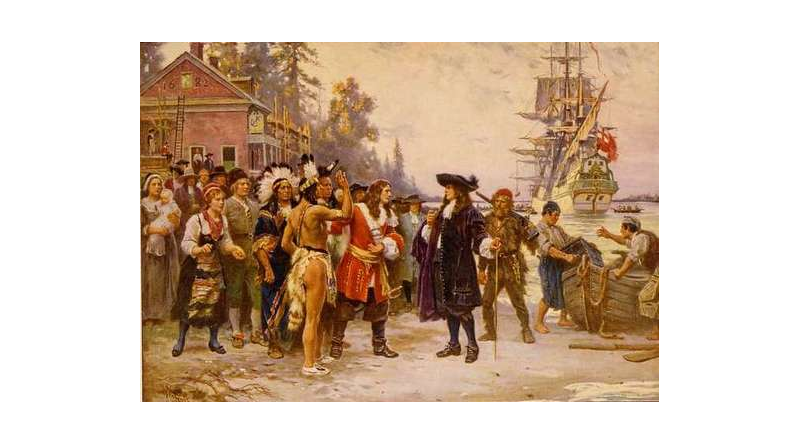

The featured image is The landing of William Penn, painted by J.L.G. Ferris between 1930 - 1932.

Delaware (founded 1638 as New Sweden; under English and Quaker control from 1664-1682)

Although small, Delaware played a significant role in the broader Quaker world. Swedish and Finnish settlements along the Delaware River welcomed travelling Quaker ministers early on, and meetings soon appeared near New Castle and along the Brandywine. When the “Three Lower Counties” came under Penn’s authority in 1682, Delaware became effectively integrated into Pennsylvania’s Quaker administration. Its assemblies, courts, and meeting structures echoed those across the Delaware Valley.

Maryland (founded 1632)

Maryland’s policy of relative toleration allowed Quakers to flourish more than anywhere else south of the Delaware Valley. Meetings grew steadily from the 1650s onward, and travelling ministers circulated easily along the Chesapeake waterways. By the late seventeenth century, Maryland hosted some of the largest Quaker communities outside New Jersey and Pennsylvania.

Virginia (founded 1607)

Virginia, with its Anglican establishment and planter elite, offered a more difficult climate. Even so, Friends appeared by the 1650s, especially in the Tidewater region, where maritime trade carried new ideas. Despite periodic fines and prosecutions, Quakers maintained meetings and contributed to local agriculture and commerce.

North Carolina (founded 1653)

The northern part of the Carolina province, especially Albemarle, became a notable centre of Quaker influence. In the 1670s and 1680s several officials were Friends, and the colony’s scattered, lightly governed settlements allowed Quaker meetings to take root. These early structures later helped shape Carolina’s political culture.

South Carolina (founded 1670)

Though smaller than its northern counterpart, South Carolina also hosted a measurable Quaker presence, particularly around Charleston. English merchants, artisans, and a handful of planters formed the nucleus of early meetings. Their numbers remained modest, but Charleston Quakers were well connected in the Atlantic network and contributed to the circulation of letters, ministers, and goods.

Throughout the century, Friends in the colonies were deeply tied to Britain and Ireland. Epistles, visiting ministers, and trade routes created a spiritual and practical network linking London, Bristol, Barbados, Newport, Philadelphia, Burlington, Charleston, and other key ports. These connections helped unify Quaker discipline across colonial boundaries and transformed early enthusiasm into a more structured, enduring movement.

By 1700, Quakers had adapted to the political realities of each colony while maintaining a distinctive identity grounded in peace, equality, and integrity. Even where they remained small in number, their influence on legal culture, trade, and ideas about liberty of conscience left a deep mark on the emerging American world.

Across the diverse landscapes of the thirteen American colonies, Quakerism spread with remarkable resilience. It faced lethal hostility in Massachusetts, flourished in Rhode Island, experimented with self-government in New Jersey and Pennsylvania, and persevered through scattered southern settlements.

By the dawn of the 18th century, Friends had established a coherent, interconnected presence from New England to the Carolinas. Their seventeenth-century witness laid foundations, legal, political, and spiritual, that would shape the future United States long after the colonial era ended.